Our Roots

FIRST UNITARIAN CHURCH HISTORY: 1836-1997

By Dr. Wallace P. Rusterholz

Updated by Dr. Margaret H. Huyck, June, 1997

CONTENTS

1836-1857

Joseph Harrington, Jr | William Adam | Rush Rhees Shippen

1857-1871

George Noyes | Robert Collyer | Charles Thomas | Robert Laird Collier

1871-1925

Brooke Herford | William Wallace Fenn | William Hansen Pulsford

1925-1980

Von Ogden Vogt | Leslie Pennington | Christopher Moore | Jack Kent | Jack Mendelsohn

1980-1997

Duke Gray | Peter Samson | Tom Chulak | Michelle Bentley | Terasa Cooley | John Gilmore

1836-1857

Our church is one of the oldest in Chicago, founded in 1836, only three years after Chicago was incorporated as a town. It began when a few young men invited a visiting Unitarian minister from Boston to talk to them and their friends in a hotel. As a result, they started our Society by adopting by-laws and planning a church building.

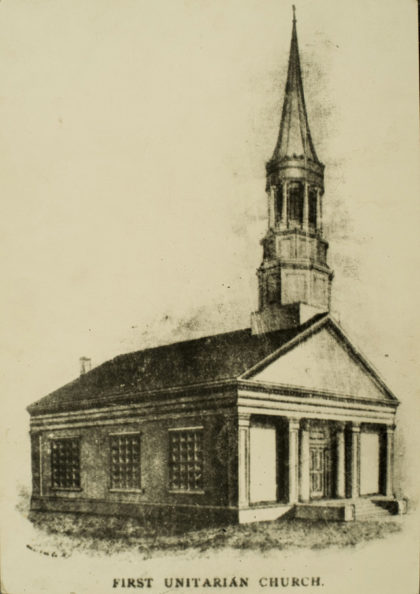

Itinerant ministers and missionaries served us in temporary quarters for three years until we called our first minister, Joseph Harrington, Jr. He was so devoted that he himself, on trips to the East, raised two-thirds of the cost of the building ($3,750). It was built in 1841 on the site of the Picasso figure in Daley Plaza.

But even though the American Unitarian Association helped our congregation by providing nearly one-third of Harrington’s salary of $1,040, we could not pay him what we had promised. So he left us in our new building after five years.

We were two years without a minister, and then called William Adam, a former Baptist missionary in India for twenty years. He filled the church, and the Society informed the American Unitarian Association that we could now be self-supporting. However, within three years the congregation had financial difficulties again, and Adam departed our Eden in 1849.

We soon called our third minister, Rush Rhees Shippen, age 21 and the first student who had enrolled in the new Unitarian seminary in his native Meadville, Pennsylvania. This is the institution which later relocated in Chicago across the corner from our church. Shippen was an outstanding minister for eight years, during which the church building was enlarged twice, his salary was almost trebled, and the Music Committee spent a thousand dollars a year. Part of the reason for this prosperity was that the Society went from voluntary contributions to the renting of pews for support of the church, a system used in most denominations in those days. With this growth, the church decided to divide, and so it sponsored the Second Unitarian Church on the North Side.

1857-1871

Shippen resigned for reasons unclear, and George F. Noyes began his brief but fruitful pastorate in 1857. He saw the need to expand the social services which the Society had begun to offer the community. So in 1859 he got the congregation to establish a Ministry-at-Large, in addition to the regular ministry, as a social service agency supported by the church and manned by volunteers. It is said to have been “the only private agency for general relief in the city at that time,” and that was when the government did little for the poor and needy.

After this Ministry-at-Large was under way, we hired as its director a man whose pioneer leadership in social work with us makes him noteworthy in the history not only of our Society and of Chicago but also of nineteenth-century America. He was Robert Collyer, an English blacksmith living in Pennsylvania, a Methodist lay preacher who had been refused a preaching license because of his heretical Unitarian and Abolitionist views.

Under Collyer’s inspired leadership, this Ministry established an outside Sunday School “distinctively for the poor” which had 200 pupils, an evening school for all ages with an enrollment of 180, sewing classes, an employment service which found 150 jobs for the unemployed, a bureau for the placement of children and the elderly in foster homes. (We should note the segregation of the poor in an outside Sunday School instead of their integration into the regular one. These poor were white, not black. Segregation then was a class, not racial, matter, as indeed it still is to a great extent.)…

Collyer graphically described his work in a letter to a friend:

“The Ministry-at-Large is devoted to the poor–to their help in every possible way…All the publicans and harlots are members of my parish (the Ministry-at-Large, not the church itself) –when all the churches turn them out and they are lost to society, I am here to help them to themselves and to God. I visit prisons and get the deserving, or those that desire to do well, into good places when they come out, or if it is better, get them out. No doubt, I am busy–just as I sit down to write this I have been out (nine at night) to get a poor woman an extension on two pawn tickets–to read and pray with a young man in consumption…and to buy meat, bread and sugar for a woman quite sick and destitute, with a drunken husband. I am kept going by the Unitarian Church…I need not be other than a Methodist to be their Minister-at-Large, but I am from conviction on the liberal side.”

Surely Collyer is one of our uncanonized Unitarian saints!

Eventually, Collyer was called away for other projects such as the U.S. Sanitary Commission in the Civil War, started by Unitarians and Universalists to care for the Northern armies. It was the precursor of the American Red Cross. Then Collyer was drafted by the new Second Unitarian Church of Chicago to be its first minister. So the Ministry-at-Large gradually faded away.

Meanwhile, Noyes suddenly resigned his pulpit in 1859 because, as he wrote to the congregation, he felt that he did not have “a free church, wherein I should be entirely untrammeled by the usual conditions of society-organization and enabled to follow, without reserve, the guidance of my own convictions of truth and duty.” What were the pressures which he felt limited his freedom? Did our Society censor his sermons or curb his self-expression? We would like to know more about this disquieting event, but the record states only that the congregation accepted his resignation with regret and appreciation for his pastorate.

Our next minister, Charles B. Thomas, arrived in 1861 from New Orleans when the Civil War began. An Abolitionist and opponent of secession, he fled to the North. He soon took the lead in planning a larger church on South Wabash Avenue near Balbo Street. It was an impressive stone Romanesque structure, but its tower promptly leaned, sank two feet, and had to be taken down. Chicago lost its chance to have a tourist attraction and its own leaning tower. The new edifice was named the Church of the Messiah, although the Society retained its original legal name which we continue to use today.

Meanwhile, despite his leadership in reviving the Society and building a new building, Thomas was dismissed for “having violated the laws of God and society and thereby become unworthy in the name of a Christian man.” Again, as in the case of Noyes’ departure, we wonder what happened behind the scenes.

Thomas was followed in 1866 by Robert Laird Collier, not to be confused with his contemporary Minister-at-Large Robert Collyer, previously mentioned. He, too, was outstanding in his pastorate. He became the active head of the Chicago Relief and Aid Society.

1871-1925

During the great Chicago fire of 1871 the church served as a refuge for the homeless. Pews were converted into beds, and food was provided in the basement Lecture Room. English Unitarians came to the aid of Chicago Unitarians, sending nearly $12,000. When we Americans feel that we always are the givers in international transactions, we should remember the astonishingly generous English of 1871.

Although the building survived the fire, the Society moved south again, building an impressive Victorian Gothic stone structure seating 1,000 people, at Michigan Avenue and 23rd Street. It was completed in 1873 at a cost of $80,000.

A year later, Collier resigned for health reasons. Two years after that, Brooke Herford of Manchester, England, became our minister. He was a popular and powerful speaker, and he stipulated that we end pew rent in favor of voluntary contributions to support the church. The women’s organization of the congregation started a free kindergarten in 1881, probably the first free one in Chicago. They gradually expanded it and even erected a building for it — certainly one of the outstanding social services in our parish history.

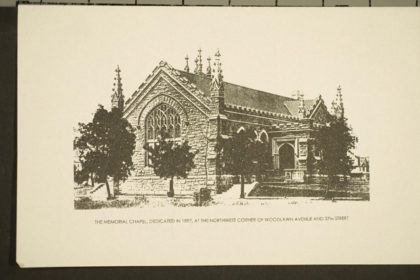

William Wallace Fenn became our minister in 1891. He saw the church’s neighborhood declining, and soon recommended that a chapel for a mission be built near the new University of Chicago. He was encouraged to do this by William Rainey Harper, the first president of the University and a Baptist. Fenn led Morton Denison Hull, long-time trustee and treasurer of the church, to build the chapel as a memorial to his parents. This was dedicated in 1897. In 1909 we sold the downtown building and moved to Hull chapel.

Fenn resigned in 1901 to become Busey Professor of Theology and eventually dean of the Harvard Divinity School. He was followed in the pulpit by William Hansen Pulsford, a Scotsman who had studied in Glasgow and Oxford Universities. He was an impressive speaker, but a poor organizer. He drew large crowds, but the congregation did not grow during his 22 years — the longest ministry in our history.

1925-1980

After an interval of two years, the modern era of our Society began in 1925 with the pastorate of Von Ogden Vogt. He was a Congregational minister in Chicago when he got the attention of Morton Denison Hull who had him invited to our ministry.

Vogt was greatly concerned with liturgy and art in religion. He was a recognized authority in this field, publishing several books, and he soon made our church what some called “high church Unitarian.” Moreover, he inspired Morton D. Hull to give us the princely gift of our magnificent stone English Perpendicular Gothic edifice. It incorporated Hull Chapel as a transept. Completed in 1931, it is our pride and joy. It was planned and designed by Hull’s son, Denison Bingham Hull, a young architect, in close and constant collaboration with Vogt who had great knowledge and interest in church art and architecture…

When Vogt retired in 1944 after nearly 20 years with us, we quickly called Leslie T. Pennington. While with us, he was a member of the Universalist-Unitarian Commission which prepared the way for the union of the two churches into one national body in 1961. At the same time, he led us in several big projects which made us leaders in our community.

The first of these was the racial integration of our Society. Blacks occasionally attended our services during Vogt’s as well as Pennington’s pastorate, and we had no formal bar to membership. But there was considerable opposition to a resolution passed at a congregational meeting in 1948 stating that we “take it upon ourselves to invite our friends of other races and colors who are interested in Unitarianism to join our church and to participate in all our activities.” Despite this clear position, a decade later we had only a dozen Black members. The number increased substantially during the next decade and later. We became an outstanding integrated congregation.

Having put our own house in order, Pennington then joined with a few others in founding the Hyde Park-Kenwood Community Conference. He was its first president. “Its purpose,” wrote Pennington later, “was reckoning directly with the issues of racial integration, community conservation and renewal, and the development here of a genuinely interracial community of high standards.” This organization led in saving the University community from becoming part of the Black ghetto all around it, although the University did not cooperate at first. This made our community an integrated model for the city and nation. But we need to remember that integration is a never-ending process…

A third big development during Pennington’s pastorate was the founding and growth of what has become the Chicago Children’s Choir under Christopher Moore. He came to us as assistant minister in 1956, with the mandate to start a children’s choir to supplement our Sunday School and attract children and families to church. He gradually built this into a huge, city-wide organization far transcending our parish and even our Hyde Park community. In addition to our Society’s support, he soon got federal money through Urban Gateways for a while, and later grants from corporations and foundations… Over the years thousands of children of all races, creeds, and social statuses were drawn into the various units of the Choir. Thus our church had an enormous outreach into the entire metropolitan area. Indeed, the Choir regularly tours various parts of the nation, and in 1970 made it’s first tour of Europe.

Chris Moore played an important role in our church, in addition to the CCC, for over thirty years until his untimely death in 1987. Whatever his title, which varied, he provided continuity and responsibility in church leadership while senior ministers came and went. His long and great service gives him a unique place in our history.

During Pennington’s pastorate, the church membership more than doubled, the Church School enrollment increased over 1,000%, the church bought the vacant lot next door and the Georgian mansion beyond that, and built the Church School building, called the Pennington Center. So in many ways Pennington’s 18-year ministry led us into great growth and direct involvement on a large scale in the community and city.

Pennington decided to retire in 1962 to a parish in suburban Boston, and we called Jack Kent the next year. During his five-year pastorate, our Society continued to concern itself with social issues and outreach to the community. We rented space to a nursery school in order to help meet a community need and utilize more fully our greatly enlarged physical plant. We made substantial contributions to the civil rights movement, housed a Head Start program, guaranteed large loans to organizations helping the poor to buy and rehabilitate slum housing, and supported our Black members’ efforts to create the Black Affairs Council in our parish and in the Unitarian Universalist denomination.

Kent resigned to take another pastorate in 1968, and Jack Mendelsohn came to us a year later with a record as a social activist as minister of historic Arlington Street Church in Boston. His ministry with us of nearly ten years was unusually successful. His social concerns reinforced ours as these had developed under the leadership of Pennington and Kent. So we proceeded to establish two large social projects, the first being the Unitarian Preschool Center which developed full day care for the children of working parents. This continued until 1979, until it had become a financial burden to us.

The second big project was The Depot. This also began in 1970 as a counseling service for runaway youth, and gradually expanded into a family counseling service with a substantial professional staff. It was headed by ministers who also were on our ministerial staff. The Depot, later named the Center for Family Development, not only got strong financial backing from the church, like the Chicago Children’s Choir, but also procured grants, donations, and contracts for counseling from government agencies. It served over four hundred families per year.

Late in his pastorate, Mendelsohn became a candidate for the presidency of the Unitarian Universalist Association. This took much of his time and energy for more than a year, but he lost a very close race.

During his ministry, we continued our concern for civil rights, especially as these are violated by law enforcement agencies during and since the so-called “Police riot” at the Democratic National Convention here in 1968. We helped to organize the Alliance to End Repression, and Mendelsohn became its president. It is a coalition of civil rights organizations which eventually won a civil suit against the Chicago police for illegal repression of voluntary organizations and protest demonstrations. The Chicago police placed Mendelsohn and our Society under surveillance for years at a cost of many thousands of dollars to the taxpayers with no results except harassment. But we should be proud that our church is not considered a “harmless” institution.

1980-1997

Mendelsohn departed to a Boston suburban parish for semi-retirement in 1978. Two years later, we called Duke T. Gray from Toronto. During his six-year pastorate, we completed the legal separation from the church of the Chicago Children’s Choir and the Center for Family Development. These projects had become too heavy financial obligations. Besides, they could receive more outside funding if not church-affiliated. But the Center had to close in 1989 because of inadequate financing. The church continues close relations with the Chicago Children’s Choir.

Although many members wished Duke Gray to remain our minister because of his excellent preaching and management, a majority of the congregation voted in 1986 to discharge him. Two years later, after an interim ministry by Peter Samson, we called Thomas Chulak from the Unitarian Universalist Association headquarters to become our next minister. He greatly revived our congregation, even to the extent of our undertaking the long delayed repair of the church steeple at a cost of a quarter of a million dollars. So we were sad when he was called away from us by the North Shore Unitarian Church of Plandome, Long Island, New York, after only three and a half years with us.

Our associate minister Michelle Bentley, a black woman, became our interim minister. This was appropriate because women have played a large role in the life our church, and blacks have done so for the last twenty years. In recent years, four chairpersons of our Board of Trustees have been black, and two of these were women. This chairpersonship of our Board is the most responsible and important position in our church. The trustees are our governing board, responsible to no hierarchy or clergy but only to our congregation, which always has the last word. Our church is truly democratic, both in theory and practice.

We called Terasa Cooley to be our minister in 1993. She came to us from Detroit, but was born in Texas. She graduated from the University of Texas and the Harvard Divinity School.

During her ministry with us, the church has gained numerous younger members, enjoys increasing participation by more members, and even a larger financial commitment to the church. We are astonished that we have fully paid for the steeple repair in only four years, and we have made a substantial start toward making the church accessible to the physically handicapped. We broaden our appeal in another way by voting to welcome to our church homosexuals, bisexuals, and transgendered people. We believe it only right that the church should welcome all who share our serious concerns. An extraordinary event was the congregation’s ordination to the ministry of a Meadville Theological School senior shortly before he died of AIDS.

In 1995 we called as our associate minister John Gilmore, an African American current graduate of Meadville/Lombard, in order to extend our outreach to the community. A year later he accepted a call elsewhere.

In 1997, Access First installed a ramp into the main sanctuary, and a wheelchair lift from the Sanctuary into Hull Chapel. These actions are part of a larger plan to make the building physically accessible to all.

The Congregation voted to participate in the Grove Parc project, working with other congregations to create and support a child care center at the housing development in Woodlawn. This is an initiative of the Social Justice Council, designed to continue the spirit of social activism so evident throughout our history.

* * * * * * * *

Epilogue (June, 1997)

At this point in our history, our Society can look back over more than a century and a half of service to our community and city. We have established and long maintained a tradition of religious and social liberalism and commitment to human values. Let us remember with gratitude and appreciation the great services to our Society and community made by our predecessors like Collyer so long ago, and of the Hull family, Vogt, Pennington, Moore, Mendelsohn and others more recently. They have led us forward and pointed the way. Now the challenge and opportunity are for us to continue the course.